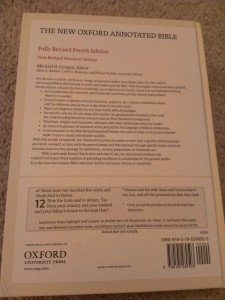

(There are two version of the New Oxford Annotated Bible (NOAB) that are available, NOAB 4th Edition in NRSV, both with and without Deuterocanonical/Apocryphal books and the NOAB Expanded Edition in the RSV)

Before we get into the review, some technical information:

Product Information

Type: Ecumenical/General Reference/Academic/Seminary-Grade Text

Translation Choices: NRSV (NOAB 4th Edition) and RSV (NOAB Expanded Edition)

ISBN for NOAB 4th Edition: 9780195289558

ISBN for NOAB Expanded Edition 9780195283488

Number of Pages (NOAB 4th Edition) 2416

Number of Pages (NOAB Expanded Edition) 1904

Features

- Wholly revised, and greatly expanded book introductions and annotations

- Annotations in a single column across the page bottom, paragraphed according to their boldface topical headings

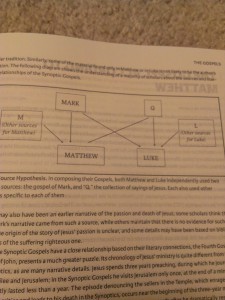

- In-text background essays on the major divisions of the biblical text

- Essays on the history of the formation of the biblical canon for Jews and various Christian churches

- More detailed explanations of the historical background of the text

- More in-depth treatment of the history and varieties of biblical criticism

- A timeline of major events in the ancient Near East

- A full index to all of the study materials, keyed to the page numbers on which they occur

- A full glossary of scholarly and critical terms

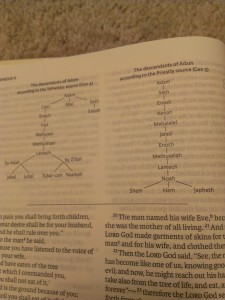

- 36-page section of full color New Oxford Bible Maps, approximately 40 in-text line drawing maps and diagrams

- 10-point type

Product Description from Oxford University Press

The premier study Bible used by scholars, pastors, undergraduate and graduate students, The New Oxford Annotated Bible offers a vast range of information, including extensive notes by experts in their fields; in-text maps, charts, and diagrams; supplementary essays on translation, biblical interpretation, cultural and historical background, and other general topics. Extensively revised (NOAB 4th Edition)—half of the material is brand new—featuring a new design to enhance readability, and brand-new color maps, the Annotated Fourth Edition adds to the established reputation of this essential biblical studies resource. Many new and revised maps, charts, and diagrams further clarify information found in the Scripture text. In addition, section introductions have been expanded and the book introductions present their information in a standard format so that students can find what they need to know. Of course, the Fourth Edition retains the features prized by students, including single column annotations at the foot of the pages, in-text charts, and maps, a page number-keyed index of all the study materials in the volume, and Oxford’s renowned Bible maps. This timely edition maintains and extends the excellence the Annotated’s users have come to expect, bringing still more insights, information, and perspectives to bear upon the understanding of the biblical text.

Classic but not stodgy, up-to-date but not trendy, The New Oxford Annotated Bible: 4th Edition is ready to serve new generations of students, teachers, and general readers.

Initial Thoughts

OUP sent me the NOAB 4th Edition in the New Revised Standard Version, without Apocrypha, free of charge in exchange for an honest review and I acquired, at my own expense, a copy of the NOAB Expanded Edition in the Revised Standard Version. Overall, I am pleasantly surprised with the NOAB and there are a number of things about it that I like.

I find myself being surprised at liking the Apocrypha. Some of it is fictional but there is a wealth of historical information regarding the segment of world history that transpired between the Old Testament and the New Testament.

Translation Choice:

The NOAB is available in both Revised Standard Version and New Revised Standard Version. Let’s look at some information on each translation:

RSV: (from Wikipedia and other sources)

The Revised Standard Version (RSV) is an English-language translation of the Bible published in several parts during the mid-20th century. The RSV is a revision of the American Standard Version (ASV) authorized by the copyright holder, the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA.

The RSV posed the first serious challenge to the popularity of the Authorized (King James) Version (KJV). It was intended to be a readable and literally accurate modern English translation, not only to create a clearer version of the Bible for the English-speaking church but also to “preserve all that is best in the English Bible as it has been known and used through the centuries” and “to put the message of the Bible in simple, enduring words that are worthy to stand in the great Tyndale-King James tradition.

The Isaiah 7:14 dispute

The RSV New Testament was well received, but reactions to the Old Testament were varied and not without controversy. Critics claimed that the RSV translators had translated the Old Testament from a non-Christian perspective. Some critics specifically referred to a Jewish viewpoint, pointing to agreements with the 1917 Jewish Publication Society of America Version TaNaKH and the presence on the editorial board of a Jewish scholar, Harry Orlinsky. Such critics further claimed that other views, including those of the New Testament, were not considered. The focus of the controversy was the RSV’s translation of the Hebrew word עַלְמָה (‘almah) in Isaiah 7:14 as “young woman” rather than the traditional Christian translation of “virgin”.

Of the seven appearances of ʿalmāh, the Septuagint translates only two of them as parthenos, “virgin” (including Isaiah 7:14). By contrast, the word בְּתוּלָה (bəṯūlāh) appears some 50 times, and the Septuagint and English translations agree in understanding the word to mean “virgin” in almost every case.

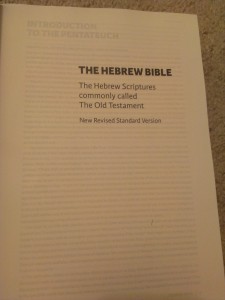

NRSV: (from nrsv.net and Wikipedia)

The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of the Christian Bible is an English translation released in 1989. It is an updated revision of the Revised Standard Version, which was itself an update of the American Standard Version.

The NRSV was intended as a translation to serve devotional, liturgical and scholarly needs of the broadest possible range of religious adherents. The full translation includes the books of the standard Protestant canon as well as the books traditionally included in the canons of Roman Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity (the so-called “Apocryphal” or “Deuterocanonical” books).

The translation appears in three main formats: an edition including only the books of the Protestant canon, a Roman Catholic Edition with all the books of that canon in their customary order, and The Common Bible, which includes all books that appear in Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Orthodox canons. Special editions of the NRSV employ British spelling and grammar.

Principles of revision for NRSV

Improved manuscripts and translations

The Old Testament translation of the RSV was completed before the Dead Sea Scrolls were available to scholars. The NRSV was intended to take advantage of this and other manuscript discoveries, and to reflect advances in scholarship.

Elimination of archaism

The RSV retained the archaic second person familiar forms (“thee and thou”) when God was addressed but eliminated their use in other contexts. The NRSV eliminated all such archaisms. In a prefatory essay to readers, the translation committee said that “although some readers may regret this change, it should be pointed out that in the original languages neither the Old Testament nor the New makes any linguistic distinction between addressing a human being and addressing the Deity.”

Gender language (This is what makes the NRSV somewhat controversial, though it is no secret that NIV and NLT do similarly)

In the preface to the NRSV Bruce Metzger wrote for the committee that “many in the churches have become sensitive to the danger of linguistic sexism arising from the inherent bias of the English language towards the masculine gender, a bias that in the case of the Bible has often restricted or obscured the meaning of the original text”. The RSV observed the older convention of using masculine nouns in a gender-neutral sense (e.g. “man” instead of “person”), and in some cases used a masculine word where the source language used a neuter word. The NRSV by contrast adopted a policy of inclusiveness in gender language. According to Metzger, “The mandates from the Division specified that, in references to men and women, masculine-oriented language should be eliminated as far as this can be done without altering passages that reflect the historical situation of ancient patriarchal culture.”

As it happens, I prefer the RSV though it is hard to explain why. The NRSV’s Old Testament is very well done, perhaps even better than the NIV as is its parent, the RSV. NRSV feels somewhat more like a Dynamic Equivalence translation even though both RSV and NRSV are essentially literal.

Content:

The supplemental articles are essentially the same in both editions, despite the fact that the last update on the RSV was in 1977. There are articles on interpretation of the text, source materials (original language texts used), contemporary methods of Bible study and others.

An estimated number of footnotes is not provided; I would guess at between 8,000-10,000 notes. They are comparable to the Harper Collins Study Bible (Incidentally a much better name is needed for this) or to the NIV Study Bible, but nowhere near the monstrous 20,000+ study notes that are provided in the ESV Study Bible. I would say that the closed comparable Bible in terms of content would be the New Interpreter’s Study Bible from Abingdon Press.

The Book Introductions are fairly brief in both versions, no more than just a couple paragraphs really. They cover mainly historical background information. I have to say that the introductions were a major disappointment for me. In a Bible that bills itself as the Academic Standard, there are some points that I would expect to see treated in the book introductions that are just not there. I would expect to see interpretive challenges being addressed, especially the “disputed” letters from Paul (Colossians and Ephesians which some question Pauline authorship of), such as in the Reformation Study Bible or the MacArthur Study Bible. I would also expect, in the Academic Standard, that you would see a section in each book introduction of how Christ is portrayed in that book and how that book fits, overall, into the Scriptures. Perhaps I am over reacting but if the point of studying the Bible is to better know Christ, then a section on how each book of Sacred Writ describes Him seems to be quite essential.

There are no conspicuous cross-references (center-column or end of verse) and I am completely annoyed by that fact; yes there are references in the footnotes but that is hardly the point. I have a number of reference Bibles that I use (first choice is Thompson Chain followed by KJV Westminster) and so, the lack of obvious cross-references is not a deal breaker for me; this too is beside the point. Most of America has one Bible and they use that daily. Oxford certainly has enough room to include center column references or end of verse references; they could even go in the gutter.

Paper, Layout, and Binding

Like Cambridge University Press, Oxford still sews its Bibles and this is an absolute must with a study Bible. The paper has a slight feeling of cotton when you touch it and I love that. The paper is more opaque in the RSV Expanded but the NOAB 4th Edition has nothing to complain about. I did not see any ghosting and I feel safe in saying that you can write in this Bible with no issues.

The text, in both Bibles, is black letter for optimum visuals, especially if you color code your notes. We have a double column for the text notes and a single column for the annotations. I actually prefer this layout as it breaks up the page nicely but still gives me that solid textbook feel.

I really wish there were wide margins; AMG was able to pull off serviceable margins for their study Bible and I am confident that if they tried, OUP could as well.

Overall Impression

My minor complaints notwithstanding, these are fairly good Bibles to own. I like it better than the Harper Collins and the CEB Study Bibles. That being said, I doubt highly that any Bible ever replaces the Thompson as my main Bible.

Should you buy the New Oxford Annotated Bible

If you are a student of the Word, yes. Any student or teacher should have multiple study resources to use when approaching the Scriptures and I can see why many seminaries consider this to be the Academic Standard. Should it be your primary Bible? I cannot answer that, except to say that I think your main Bible should be as free as commentary as possible. As my mentor Doug tells me, “I want to hear what God has to say to me first. Then I will see what he told someone else.” I could not agree more. Study Bibles are a good, valuable tool when used properly but no source of commentary should ever be consulted before the Holy Spirit; if He can write the book and preserve it for thousands of years, He can certainly tell you what he means.

NOAB Expanded Edition (RSV) Photos

NOAB 4th Edition (NRSV) Photos

I have both of these books and your review captured the excellence of both volumes. Thanks for displaying these volumes as they are very useful in getting to the meaning of the biblical text. I always have them nearby. Both are great reads, scholarly, and nicely laid out.

Dear Friends:

I have read lots of commentary on the bible, and knowing from the outset that the commentary is a person, or persons opinion, have found such writings valuable. I especially like Matthew Henry’s commentaries. Having said that, I’m relucant to call it a bible. It is too easy to get the commentary and the text mixed up, at least it is for me. We all want some aids in our bibles, just how much is the question. I can understand cross referrences, notes from translators, dictionaries, imbedded and standard formats, appendicies with notes about customs, money, maps geography letters of Christ in Red etc. But when the commentaries are imbedded in the bible itself, I find that it is too much for me. Aids are one thing, an inbedded commentary is perhaps “A bridge too far”. I think it is best to let the bible itself interpret it’s contents. It takes a little more effort, but when done, the opinion gained is one’s own, not what someone else tells you it is. I have developed the habit of having my commentary in seperate books from the bible itself, and resort to these only when I have to. My opinions, my habits, they work for me, I think I will continue as I have done for many years now.

Yours in Christ

Don Denison

Hi Don,

I feel the same way about commentary. I’ve never felt comfortable using a study Bible except for some general reference work. Many times, the verse I’m looking for doesn’t have a comment anyway because of limited space. They can be great study tools but it shouldn’t take the place of your own study.

The NOAB (4th edition from 2010) using the NRSV is great in terms of the all the up-to-date scholarship that it offers the reader. But it isn’t traditionally sewn and bound in any of the editions available, even the leather one.

Actually it is sewn. Both OUP and my own physical inspection revealed that both of the editions that I reviewed are sewn bindings.

“Perhaps I am over reacting but if the point of studying the Bible is to better know Christ …” Well there’s your problem. That’s not the reason for anyone who wants an honest, scholarly translation that lacks an overt bias. If the translator is already Christian, then s/he is resistant to any information found in sources that contradicts his/her preconceived expectations. Because bible stories have infiltrated so much of Western culture, they’re worth being aware of, but no honest person pretends they depict “spiritual truth.”